Ubisoft, the maker of the Assassin’s Creed videogame, is suing John L. Beiswenger for a court ruling that its Assassin’s Creed video game does not infringe Beiswenger’s alleged copyright in the “Link” novel. In April, Beiswenger sued Ubisoft for copyright infringement in Pennsylvania seeking $5 million in damages and tried to stop or enjoin Ubisoft from releasing Assassin’s Creed III in October of 2012. On May 29, 2012, Beiswenger voluntarily dismissed his copyright infringement claim “without prejudice,” which means that he could re-file the complaint at any time. Ubisoft filed its complaint on May 30, 2012 in California to have the Court rule — once and for all — that Beiswenger’s copyright infringement claims are “entirely meritless” and that there’s no infringement.

Ubisoft, the maker of the Assassin’s Creed videogame, is suing John L. Beiswenger for a court ruling that its Assassin’s Creed video game does not infringe Beiswenger’s alleged copyright in the “Link” novel. In April, Beiswenger sued Ubisoft for copyright infringement in Pennsylvania seeking $5 million in damages and tried to stop or enjoin Ubisoft from releasing Assassin’s Creed III in October of 2012. On May 29, 2012, Beiswenger voluntarily dismissed his copyright infringement claim “without prejudice,” which means that he could re-file the complaint at any time. Ubisoft filed its complaint on May 30, 2012 in California to have the Court rule — once and for all — that Beiswenger’s copyright infringement claims are “entirely meritless” and that there’s no infringement.

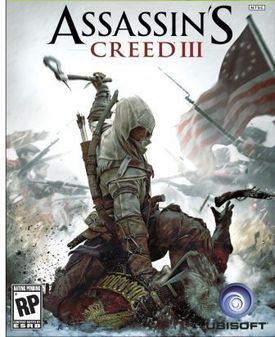

Ubisoft is very interested in keeping its Assassin’s Creed videogame franchise out of copyright infringement purgatory because since its first release in 2007, the game has been “a critical and financial success” and evolved into three more video games, including the upcoming October release of the fifth videogame in the series entitled Assassin’s Creed III. In the games, players “take on the role of Desmond Miles, a man who is imprisoned and forced to relive the experiences of one of his ancestors, Altair ibn La’Ahad.” Ubisoft claims that accessing the experiences of an ancestor is the tenuous copyright infringement claim, which access was accidently invented in the novel “Link.”

In the Prior Action, Beiswenger claimed that Ubisoft has infringed the copyright in Link because among other things: (i) both Assasin’s Creed and Link contain such archetypal elements as”‘spiritual and. biblical tones,” make use of the, age-old theme of “good vs. evil,” and contain references to such generic, stock terms as “ancestors,” “synchronize,”and “assassins;” (ii) both feature main, characters who talk in the first person;” and (iii) both concern a “device and process” by which characters are able to access and relive the memories of their ancestors.

Ubisoft alleges that narrative devices, such as speaking in the first person, the generic theme of good vs. evil, and accessing ancestral memories are not actionable under any copyright theory. Ubisoft also contends that the idea of accessing ancestral memories predates the publication of either Link or Assassin’s Creed and “can be found in such well-known prior art as Frank Herbert’s Dune series of novels and short story, The GM Effect, the Doc Savage novel, They Died Twice, Douglas Adams’ 1979 novel, The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy, the 1975 television series, The Invisible Man, and John Carpenter’s 1982 film, The Thing, to name just a few.” In addition, Ubisoft claims that Assassin’s Creed and Link contain numerous and substantial dissimilarities so that copying cannot be established.

Because Beiswenger’s previously filed copyright infringement claim was dismissed “without prejudice” and his attorney could not confirm that it would not be re-filed, including on the eve of Assassin’s Creed III‘s launch, Ubisoft states that an actual “case or controversy” exists necessitating a Court’s declaration of non-infringement. See MedImmune, Inc. v. Genentech, Inc., 549 U.S. 118 (2007).

The case is Ubisoft Entertainment, SA, v. John L. Beiswenger, CV12-2754 NC (N.D. Cal. 2012).

Los Angeles Intellectual Property Trademark Attorney Blog

Los Angeles Intellectual Property Trademark Attorney Blog