In a complaint that should have been written by quill on a wax-sealed scroll instead of pleading paper, Baron Philippe de Rothschild S.A. and Société Civile du Château Lafite Rothschild (you may now bow or curtsey), companies owned by the Rothschild Family (whose ancestors were ennobled by European monarchies), are suing an alleged commoner, Judson Rothschild, for trademark infringement and cybersquatting for using the surname and Coat of Arms to hock furniture and interior design services to both noblemen and commoners alike. As full disclosure, I am not ennobled by European monarchies. Instead, my father enjoyed reading Shakespeare, thus the name: Milord.

In a complaint that should have been written by quill on a wax-sealed scroll instead of pleading paper, Baron Philippe de Rothschild S.A. and Société Civile du Château Lafite Rothschild (you may now bow or curtsey), companies owned by the Rothschild Family (whose ancestors were ennobled by European monarchies), are suing an alleged commoner, Judson Rothschild, for trademark infringement and cybersquatting for using the surname and Coat of Arms to hock furniture and interior design services to both noblemen and commoners alike. As full disclosure, I am not ennobled by European monarchies. Instead, my father enjoyed reading Shakespeare, thus the name: Milord.

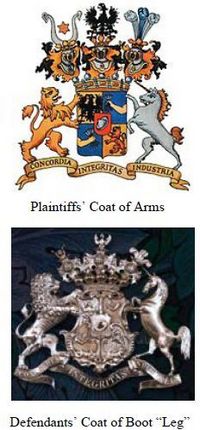

Plaintiffs allege that the family is engaged in numerous international businesses, including “two of the most famous wine enterprises in the world, and own the estates which produce the well-known ‘Chateau Mouton Rothschild’ and ‘Chateau Lafite Rothschild’ wines. These wines have become known as the finest of Bordeaux wines, and command a price appropriate to their quality.” Plaintiffs own several USPTO registered trademarks incorporating the surname, including Chateau Lafite-Rothschild, Chateau Mouton Rothschild, and Baron Philippe de Rothschild.

“As a result of the activities of the plaintiffs and their predecessor entities, and the well-known history of the Rothschild Family, the Rothschild name has become well known in the United States and throughout the world in connection with luxury goods.” Plaintiffs also allege that “because of the association of the Rothschild Family and their enterprises with opulent decoration, there are numerous literary references to ‘the Rothschild style’ or ‘the style Rothschild.’ The term has become part of interior decorators’ language.” Further, plaintiffs contend that the family’s coat-of-arms is famously associated with the Rothschild name and has developed secondary meaning in connection with products denoting luxury and comfort.

Los Angeles Intellectual Property Trademark Attorney Blog

Los Angeles Intellectual Property Trademark Attorney Blog

Aevoe has filed a trademark infringement and false designation of origin lawsuit against numerous entities accused of selling iPad and iPhone accessories bearing its

Aevoe has filed a trademark infringement and false designation of origin lawsuit against numerous entities accused of selling iPad and iPhone accessories bearing its